OUR QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER TO CLIENTS AND FRIENDS OF THE FIRM

FIRST QUARTER 2024

Markets Thrive Amidst Uncertainty

What a remarkable start to the year it has been for US stocks! Despite facing significant challenges with inflation, interest rates, oil prices, and even geopolitical conflict, the S&P 500 notched its largest first-quarter gain since 2019. Even as Germany, Japan, and England risk slipping into recession, the S&P 500 has continued to climb higher. Factors contributing to this resilience can be viewed from two perspectives: specific company-level developments and broader economic trends.

At the company level, there was continued investor enthusiasm for the potential of generative artificial intelligence. Investors increasingly recognized the transformative impact of this technology, driving optimism about long-term productivity gains.

On a broader economic scale, the rally’s expansion was fueled by factors such as US economic strength, the Federal Reserve’s accommodative monetary policy stance, and the pause in interest rate hikes. With the growth of the US economy outpacing many others in 2023, confidence in US economic exceptionalism soared and fueled further market gains. All this combined with Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s reassurance that the inflation outlook remained largely unchanged, despite temporary spikes, has also helped ease concerns among investors.

The resilience of US stocks in the face of global challenges underscores the complexity and opacity of market dynamics. A diversified, long-term approach to investing designed to weather all markets has been and will continue to be the Ariadne way.

Do Elections Impact the Stock Market?

Politics and economic prosperity are much less connected than the press might have you believe. As the 2024 presidential election looms large, investors often contemplate its potential impact on financial markets.

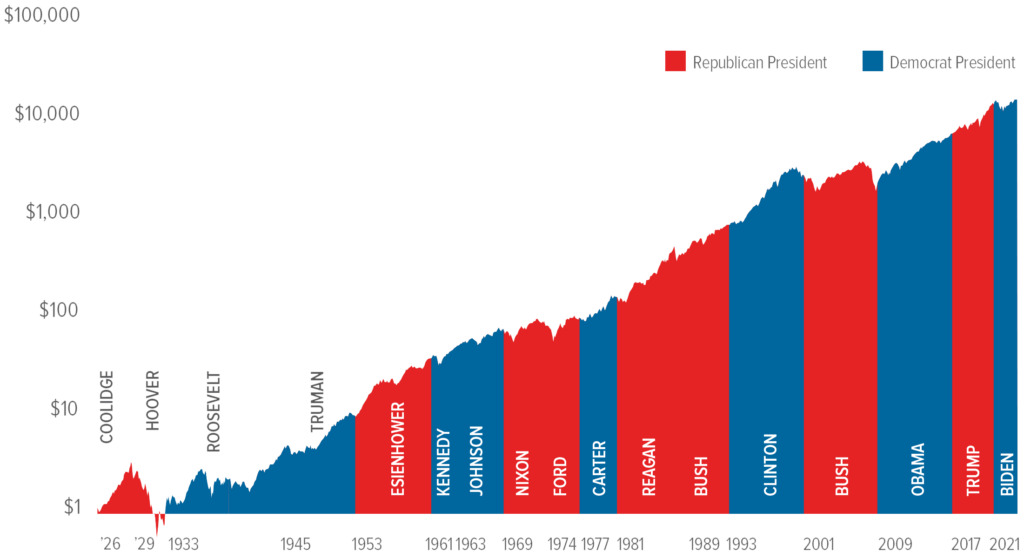

As with every investment, it’s useful to take a look at the historical data. Analysis reveals a compelling pattern: the S&P 500 has delivered positive annual returns in 20 out of 24 presidential election years from 1932 through 2020. As seen in Figure 1, regardless of the political affiliation of the incoming administration, markets have historically rewarded disciplined investors over the long term, underscoring the disconnect between political party and investment performance.

While the political landscape may shift, the fundamentals of sound investing remain steadfast. Rather than being swayed by short-term fluctuations, investors are encouraged to adopt a rational approach, anchored in empirical evidence. As the countdown to November 5 begins, let us remain constant in our knowledge that whichever party presides over the Capitol, markets will continue to function as they always have.

Figure 1

THE MARKET AND US PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS

Hypothetical Growth of $1 invested in the S&P 500: January 1926-March 2024

Does Debt Matter?

The US debt-to-GDP ratio has become an everyday topic in economic discussions. When interpreting this ratio, a higher number means that a country has taken on more debt relative to its Gross Domestic Product, a measure of how productive an economy is. As seen in Figure 2, the US debt as a percentage of GDP is higher than any point in history.

While it might seem intuitive that increasing debt burdens could hinder market growth, historical analyses reveal an uncertain correlation between the debt-to-GDP ratio and stock returns. Multiple factors such as interest rates, economic growth trajectories, governmental policies, and market sentiment all play a role as well.

Counterintuitively, Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) argues that countries can manage large deficits without dire consequences, emphasizing the importance of controlling inflation over fixating on debt levels. This theory has stirred heated debate, challenging the prevailing belief that high government debt is inherently harmful. Critics of MMT raise concerns about the risks of unchecked government spending, warning of potential inflationary pressures, currency devaluation, and economic instability.

A recent example when these concerns came to a head was in October 2022 when UK Prime Minister Liz Truss implemented a cavalier approach to her country’s debt. Under her leadership, the UK saw its debt-to-GDP ratio surge, leading to record-low values for the Pound and causing borrowing costs to spike. Amid fears of economic chaos, Truss’s popularity plummeted, culminating in her resignation after just seven weeks in office. Clearly, not everyone agrees that MMT is the way forward.

Whether a nation’s debt truly matters or not is still a matter of debate, but here at Ariadne our portfolios are crafted to adapt to either case.

Figure 2

GROSS FEDERAL DEBT AS PERCENT OF GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT

Percent of GDP, Annual, Not Seasonally Adjusted 1926-2023

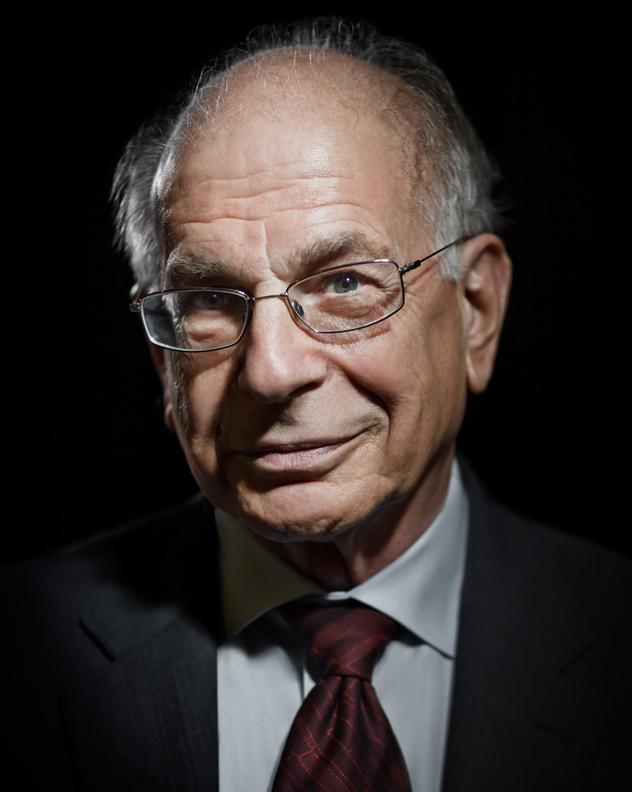

Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman Left An Important Message On Market Psychology

By Hersh Shefrin

April 8, 2024

The late psychologist Daniel Kahneman had an important message for investors, analysts, and economists: Be careful when you treat the market as if it were a person.

Kahneman, who passed away this past March, was a Nobel laureate in economics. He received the accolade in 2002. That year, he also

gave a presentation at Northwestern University, and discussed investors’ tendency to personify the market. Below are excerpts from that event.

Kahneman: Does The Market Have A Psychology?

This talk is meant to be about psychology and the market.

If you listen to financial analysts on the radio or on TV, you quickly learn that the market has a psychology. Indeed, it has a character. It has thoughts, beliefs, moods and sometimes stormy emotions.

The main characteristic of the market is extreme nervousness. It is full of hope one moment and full of anxiety the next day. It often seems to be afraid of economic good news, which make it worry about inflation, but soothing words from the chair of the Fed make it feel better.

The market is swayed by powerful emotions of like and dislike. For a while it likes one sector of the economy, but then it may become discouraged, suspicious, and even hostile.

The market is generally quite active, but occasionally it stops to take a breather. And sometimes it catches its breath and takes profits. In short, the market closely resembles a stereotypical individual investor.

Kahneman: What Accounts For The Tendency To View The Market As A Person?

The tendency to ascribe states of mind to entities that don’t have a mind is a characteristic of an early phase of cognitive development, as when a child says that the sun sets because it is tired and going to bed. And we can recognize it in ourselves as grown-ups: when I play Snakes and Ladders, it is sometimes hard to avoid the impression that this green object is full of energy, whereas the yellow one is a bumbling mess that will never get anywhere.

Why do adults engage in this kind of animistic thinking about the market? What does it do for them? I am arguing, of course, that this thinking happens automatically. But it also has a function, as a way of making sense of the past, which creates an illusion of intentionality and continuity. I am using intentionality here as philosophers do, to denote beliefs as well as desires.

The personification fosters an illusion of predictability. The point is that intentional interpretations of behavior generate expectations of future behavior. And it is a psychological fact that the tendency to produce such expectations will persist indefinitely, even if they are reinforced on a strictly random schedule.

Kahneman: Does The Theoretical End Justify The Theoretical Means?

Analysts are not the only ones who think of the market as a person. People who write models with representative agents obviously do something of the same general kind. Some of my best friends have written such models.

As a psychologist I have always liked these models, especially when they are written in a language I understand.

But this is an instance in which my friends do something that they oppose and even ridicule in other contexts. They make assumptions that they know are not true, just because these assumptions help them reach conclusions that make sense.

In fact, of course, agents are not all alike and the differences among them surely matter.

Realism will be improved by having two types of agents, with different psychological makeups.

Kahneman: How Do Institutional Investors and Individual Investors Compare?

If I have time, I will speculate in a completely irresponsible fashion about possible similarities and differences between individual and institutional investors.

We know from Terry Odean’s famous result that individual investors pay about 3.4% plus transaction costs whenever they have a significant idea about changing their portfolio. It seems plausible that there is someone on the other side of these transactions, and likely that these are institutions.

Terry and Brad have begun to investigate some plausible hypotheses about differences in the trading behavior of individuals and institutions.

They seem able to do very well without any real inspiration from psychology, but I think that an effort to find out which psychological principles that describe representative individuals also apply to representative institutional investors, is very worthwhile.

I should report on preliminary results from research I undertook by taking Burt Malkiel to lunch. He actually does not believe that institutions are smarter than individuals. But this may not be the last word. For example, Burt could not answer my question about whether the disposition effect also applies to institutions.

Conclusions:

In his long career, Kahneman left much for us to ponder about financial vulnerabilities. The need for care when personifying the market is a case in point. He wanted us to realize that individual investors, institutional investors, analysts, and economists are all prone to the illusion of predictability.

Disclosures: Past performance is no guarantee of future results

Figure 2 Sources OMB; St. Louis Fed